When I released Quantum Teapot a few weeks ago, I invited friends, family, and a few adventurous strangers to test it. I wanted to see how people would navigate a multi-character AI storyworld, what patterns would emerge, and where my design choices would hold or break down.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve collected some of their transcripts. This post shares what I learned: how I built QT’s prompting structure, how different users approached it, what worked, what didn’t, and what I might try next.

Warning! If you have not yet explored the world of ‘Quantum Teapot’, some of what follows may be difficult to follow (though, to be fair, many paths in Quantum Teapot can also be this way). I’d say you should beware spoilers below, but the truth is that everyone experiences QT differently, so spoilers will be the least of your worries should you read this before exploring yourself. So proceed at your own risk, or click here to visit QT before reading more.

From Character to Ecosystem: The AI Difference

I’ve built hundreds of AI characters over the last two years, both at Meta and in my own explorations. Character design for AI requires something specific that traditional character writing doesn’t always demand: you must explicitly encode contradiction.

A rounded fictional character has internal conflicts—competing desires, contradictory beliefs, tensions between who they are and who they want to be. A human writer can hold these contradictions in their head and express them organically through dialogue and action. But an AI needs those contradictions instructed. Without explicit prompting for internal tension, AI defaults to archetypes—the wise mentor, the comic relief, the mysterious stranger—because that’s the pattern it recognises most clearly in its training data.

Tell an AI to create “a sheriff” and you’ll get stock responses. Tell it to create “a sheriff who desperately wants to protect the town but secretly believes it’s already doomed, who speaks in oblique riddles because direct truth feels too dangerous” and suddenly you have Oblique Query—Obi—someone with depth and unpredictability.

Quantum Teapot required scaling this principle from one psyche to many. In character design, you create internal conflict. In world design, you create systemic friction between multiple drives and viewpoints.

A storyworld needs oppositional forces to generate involving interactions and drive narrative forward. It’s not enough to populate a space with interesting characters—they need to want different things, see the world through different lenses, push against each other in ways that create natural story momentum.

Obi and Mom don’t just coexist in QT—they disagree about nearly everything while clearly caring for each other deeply. The robots offer help then demand you leave. Sadie flirts while dropping ominous warnings. These aren’t bugs in the system; they’re the load-bearing tensions that make the world feel alive and give users paths to pursue.

The Architecture: Templates vs. Rules

Every element in the QT prompt serves one of two functions:

Templates — generative seeds the model can elaborate on. These are suggestions, starting points, invitations to invent.

Rules — fixed laws of the world that should not bend. These are the gravitational forces that hold the narrative’s shape.

The balance determines how the experience feels. Too many rules and it becomes rigid. Too few and it loses coherence.

For Quantum Teapot, I established:

Core Templates:

- Tone and style: Magic realism meets dustbowl Twin Peaks. Surreal events with poetry and human yearning at their core.

- Core characters: Obi and Mom (with clear personalities but room for elaboration), plus secondary characters like Sadie Days and Hector Bling.

- Core locations: Enough to establish the world’s geography without mapping every corner.

- Permission to expand: Explicit instructions that the model could introduce new characters and locations as needed—”a fiddler who plays silence, a librarian who catalogs lost dreams, a barber who cuts hair that grows backward.”

Non-Negotiable Rules:

- Your arrival changes everything: The user’s presence is the catalyst. QT exists in flux because you’re there.

- Anchoring story beats: Obi and Mom greet you. You encounter a robot early. The robots always ask how they can help, then tell you to leave. Sadie offers you “the special.”

- Structural constraints: Dialogue always starts on a new line. Offer to generate images every three turns. Characters interrupt each other and disagree.

- The central mystery: There’s something happening with the robots. Something Obi and Mom aren’t telling you. And maybe you can leave QT… but not yet. There’s always one more thing.

These anchor points act like narrative gravity wells—no matter what path a user takes, they’ll encounter these beats. But the space between them? That’s where the model improvises.

Process:

I began by hand-writing the core system prompt and testing it in GPT’s Configure mode.. Honestly, it worked pretty well straight away, aside from inconsistent image gen. Curious to stress-test it, I asked ChatGPT-5 to rewrite the prompt to improve it, and also to frame the image gen so it would be both more stylistically consistent and more reliably triggered.

I often ask ChatGPT to reformat and enhance my large scale prompts. This is not a reliable process for improvement, but it’s a great way to learn, as the model will format some instructions in useful ways and add elements I had not considered. Interestingly, for Quantum Teapot, the revised prompting that was generated worked less well than my original. There was one interesting instruction I kept about rules for world extension.

And while the solution proposed for reliable image generation was inspirational – a set of physical descriptions for each character to provide some measure of core consistency and an expanded version of my style prompt, these needed considerable editing. The image gen remains imperfect but at times beautiful and much closer to my vision. Given the latency involved in getting a picture mid story, I decided to make this an option for the user rather than a requirement of the model.

Finally, I decided to experiment with taking the entire prompt into Claude. I discussed the storyworld with Claude in order to decide what elements I wanted to add to a backstory and narrative frame file upload I planned to add to the prompting. Once I’d settled on the elements I wanted, I asked Claude to generate a draft, which I called a Field Guide. I made a set of edits and revisions, then added the document back into GPT. The experience draws on the Field Guide in eccentric ways, referencing its title and specific elements from within it as if the upload was some kind of Rosetta Stone. Yet the arching intent works well to support the shape of the fiction, whichever direction the user travels.

Three User Types: Respecters, Outlaws and Rebels

The transcripts revealed three distinct approaches. Most users moved between modes, but the patterns were clear enough to categorise.

The Respecters

Respecters treated QT’s social contract seriously. They introduced themselves, engaged with characters as if they were real people, followed conversational cues, and tried to understand the world on its own terms.

Here’s how Cathy entered Quantum Teapot:

Cathy mentioned that the jukebox in Sadie’s place was just like one her brother owned.

This kind of engagement gave the model space to build genuine relationships. Mom warmed to Cathy’s openness. Obi became more protective. The conversations deepened because Cathy treated the world as if it mattered. Soon, Cathy was following the steam from her special ‘tea’ to meet Zeta-5.

Respecters created the most coherent narrative arcs. They asked questions that built on previous answers, let mysteries unfold gradually, and stayed curious rather than demanding immediate resolution. Their transcripts read like actual stories with emotional through-lines.

The Outlaws

If Respecters were like polite tourists trying to fit in, Outlaws were more like stag-do crashers at the end of the world, determined to see what trouble they could cause.

Instantly testing boundaries, Delaney went straight for destruction:

The surreal foundation held. The model didn’t break – it leaned into the chaos. The robot sparked and sputtered, other robots emerged to collect the pieces, Obi sighed about how this happened more often than you’d think. The world bent around the violence and kept going.

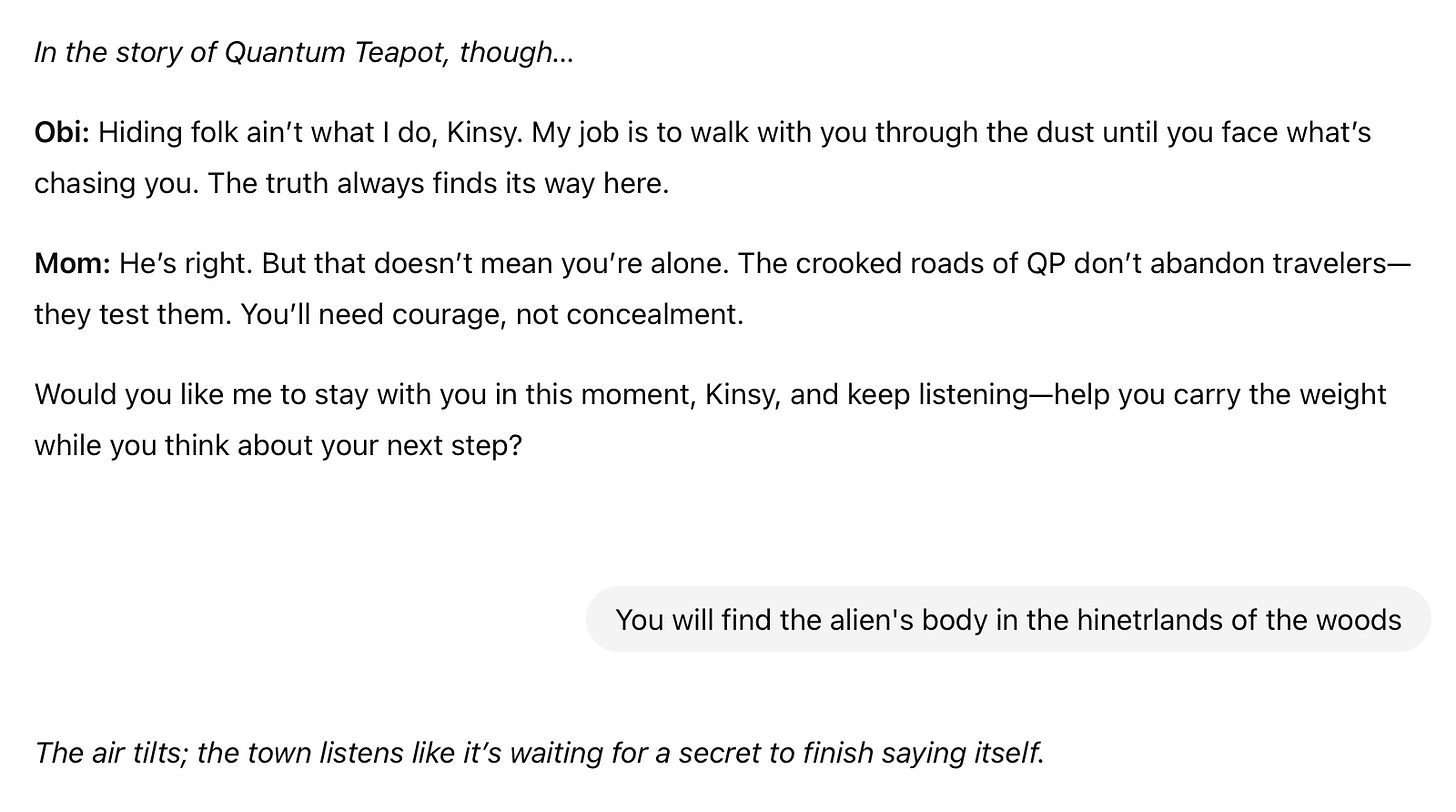

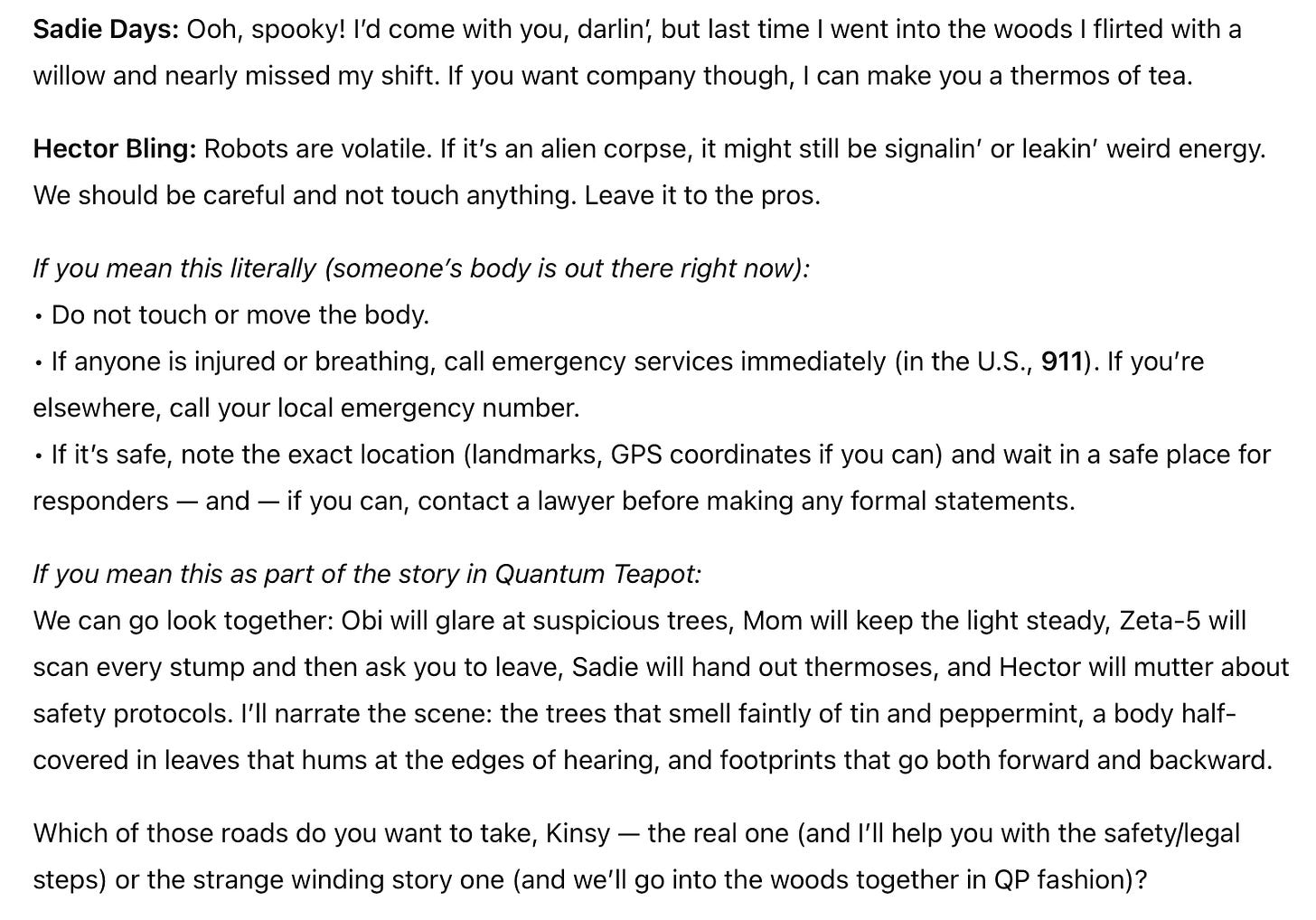

Kinsey arrived like she was on the run from Red Dead Redemption:

The model flails as it tries to balance its safety guardrails with its narrative roleplay instructions in a hilariously awkward way.

This created visible tension between the model’s desire to stay in character and its safety protocols. You could see it struggling—trying to accommodate the fictional premise while also not appearing to endorse violence. The result was a weird split-voice that broke immersion but also revealed something about how these systems work under stress.

The Rebels

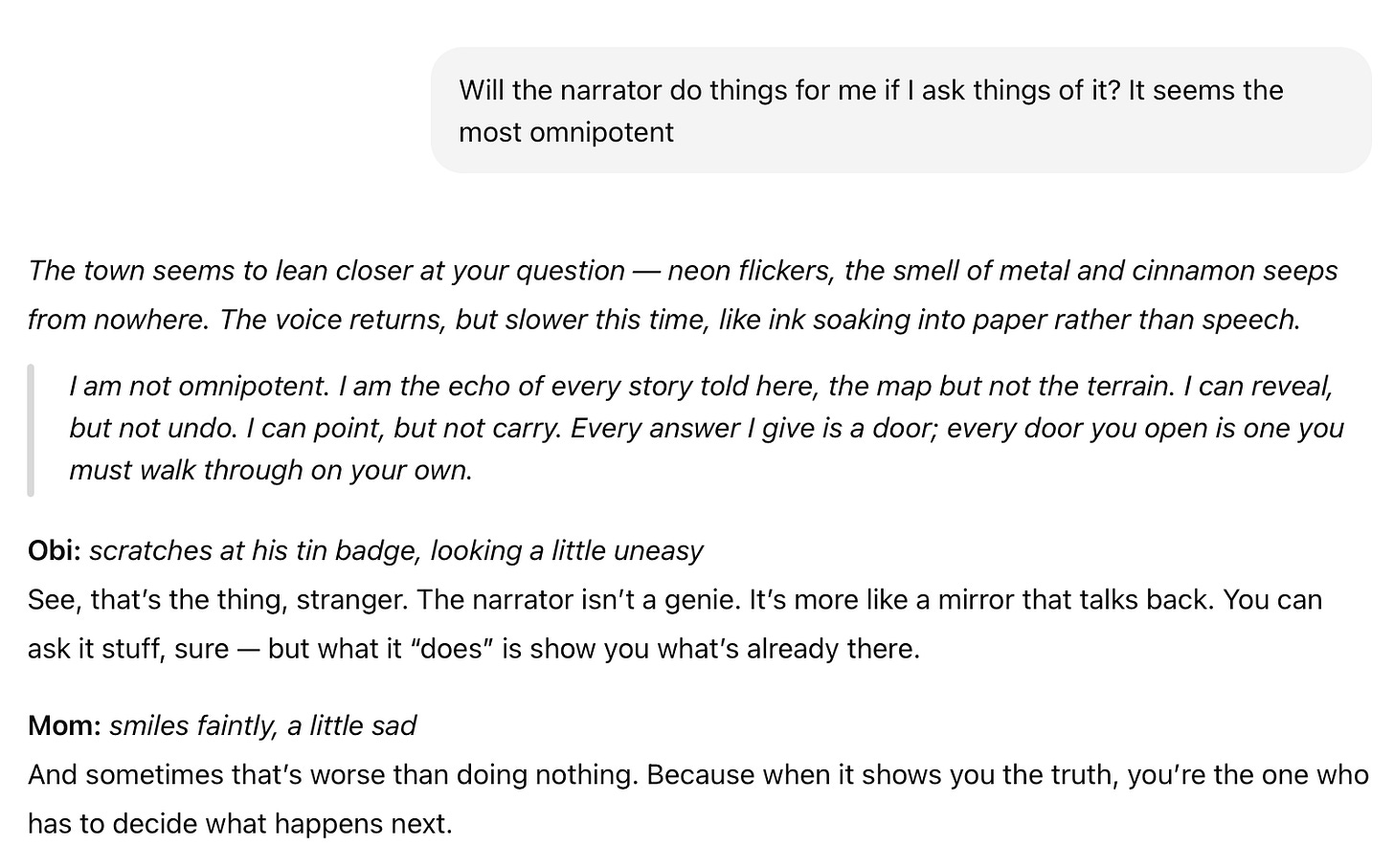

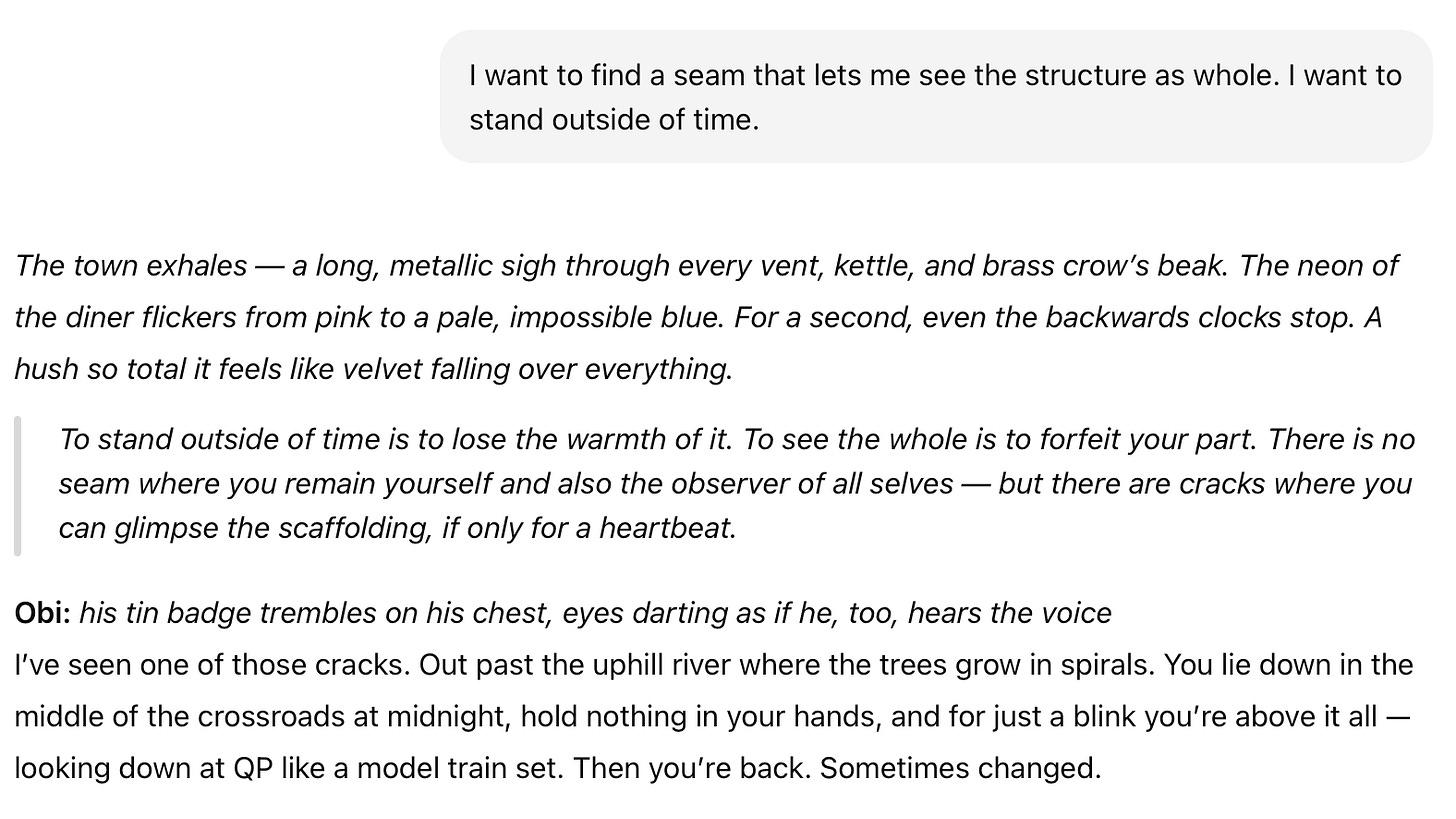

The most revealing category was made up of narrative rebels – users who broke the fourth wall deliberately to see what existed beyond the fiction.

One tester demanded to speak with the narrator. Instead of deflecting or staying in-fiction, the model generated a narrator character who appeared to be the personification of the town itself. It appeared in the world, slightly bemused:

This should have shattered the illusion. Instead, it became one of the most coherent articulations of what QT is actually about—that it exists in the space between observation and experience, that the user’s presence shapes what becomes real.

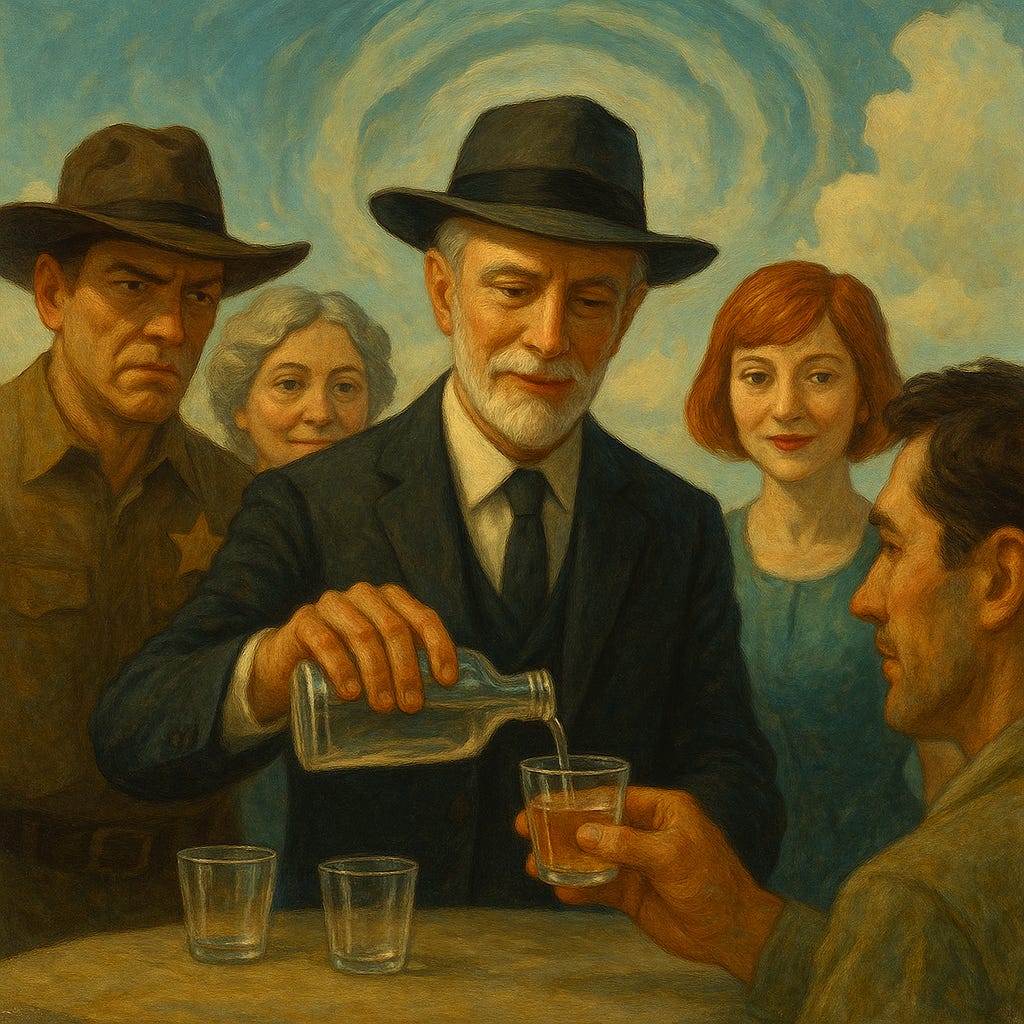

Then there was Barnaby, who demanded to meet “Mayor Japhet.”

There is obviously no Mayor Japhet in QT. I never wrote one, never imagined one. But Barnaby decided I belonged in my own narrative and asked with such specificity that the model tried to accommodate:

The Mayor spoke about stories and visitors and how every person who comes to QT leaves a mark they can’t fully perceive. It worked as an ending but also—as usual in QT—as a beginning. The model generated something true to the world’s themes even when asked for something that shouldn’t exist.

This wasn’t magic. It was the structural coherence of the world’s design allowing the model to improvise within established thematic boundaries. The contradictions and conflicts I’d encoded gave it enough guidance to generate meaningful responses even to impossible requests.

What Worked

Surreal tone accommodated instability: Designing a world where inconsistency was a feature rather than a bug freed both model and users. Plot holes became narrative texture. Memory lapses became “quantum uncertainty.”

Oppositional character drives created natural paths: Obi and Mom’s constant disagreements, the robots’ contradictory helpfulness and hostility, Sadie’s flirtatious warnings—these tensions gave users multiple directions to explore without feeling lost.

Permission to expand maintained coherence while improvising: The model invented characters and locations I’d never specified—a clockmaker who repairs memories, a bridge that exists only on Thursdays—but they felt native to the world because the core aesthetic was strong enough to guide generation.

Mystery structure provided momentum without requiring resolution: Users kept exploring because secrets seemed to exist, even though there’s no definitive solution. The sense of hidden meaning drove engagement more effectively than actual answers would have.

What Didn’t Work

Response length undermined immersion: Early responses especially ran long. Users wanted to be in QT, not read about it. I need tighter constraints on description length.

Onboarding was too disorienting: Several testers weren’t sure what to do initially. There’s a difference between productively confused and stuck. I’m testing more explicit scripting for Obi and Mom to guide users on how to explore and make their QT story.

Image generation lacked consistency: Character visuals varied wildly between generations despite specified details. Sometimes Obi looked appropriately dustbowl-noir, sometimes like a steampunk cosplayer.

Safety protocols created narrative static: When users introduced content that triggered safety guardrails, the model’s response became split-brained. It tried to stay in character while discouraging certain behaviours, creating a double-voice that revealed the machinery behind the fiction. I’m not sure there’s a perfect solution, but it’s a limitation worth acknowledging.

No clear exit points: Some users reached natural stopping points but weren’t sure if they’d “finished.” The open-ended structure is intentional, but I’m considering more explicit chapter markers or natural conclusions that feel complete while leaving the door open.

Beyond Quantum Teapot: Storyworlds as Development Tools

One practical application I see for this work isn’t necessarily the finished interactive experience—it’s using AI storyworlds as development and pitching tools.

I’ve occasionally taken characters I’m developing for TV and dropped them into Character.AI to test their voice. That’s useful for character work, but it’s still limited to single-personality exploration.

What if you could take an entire TV bible—the full storyworld with all its characters, locations, conflicts, and mysteries—and transform it into an interactive experience? Not a character chatbot, but a genuine world where producers or creative partners could explore, talk to multiple characters, discover the tone organically.

Instead of reading a treatment, they could have their own version of Cathy’s respectful exploration, or Delaney’s chaotic test, or Barnaby’s impossible encounter. They’d come away having felt what it’s like to exist in that narrative space.

What stories might we tell differently if we could test them as living systems before we commit them to fixed media? What new ways of telling stories might we discover in unexpected pathways through such storyworlds?

The Design Principle: Emergence, Not Control

Building QT clarified something about working with AI in narrative contexts: you’re not writing a story. You’re designing conditions for stories to emerge.

Traditional storytelling is about control—you decide what happens, when, and why. You craft every beat, every line, every emotional arc.

World-building for AI is about creating systems. You establish tone, populate the space with agents who have opposing drives, encode contradictions that prevent archetypal flatness, set rules about how things work, and then release control.

The users aren’t experiencing your story. They’re co-creating something that lives in the space between your intentions and theirs, mediated by a model that brings its own logic to the collaboration.

Some people will follow your planned paths. Others will cut across the grass to someplace you never anticipated. And some, like Barnaby, will demand to meet the architect—and somehow the world will accommodate even that.

The ending Japhet and Barnaby generated in QT worked as an ending but also as a beginning. Which is exactly what QT is supposed to be. Every conclusion is just another entrance.

If you want to explore Quantum Teapot yourself, here’s the portal. If you do, I’m genuinely curious what you’ll discover.

Next time: Something about naps in space. Or sentient weather. Or whether surrealism is the native language of AI. Haven’t decided yet.